Implementing and Understanding Cosine Similarity

I get a lot of questions from new students on cosine similarity, so I wanted to dedicate a post to hopefully bring a new student up to speed. I’m including a (not so rigorous) proof for the background math along with a rather naive implementation of cosine similarity that you should probably not ever use in production.

Why should you care about cosine similarity? In practice, cosine similarity tends to be useful when trying to determine how similar two texts/documents are. I’ve seen it used for sentiment analysis, translation, and some rather brilliant work at Georgia Tech for detecting plagiarism. Cosine similarity works in these usecases because we ignore magnitude and focus solely on orientation. In NLP, this might help us still detect that a much longer document has the same “theme” as a much shorter document since we don’t worry about the magnitude or the “length” of the documents themselves.

Intuitively, let’s say we have 2 vectors, each representing a sentence. If the vectors are close to parallel, maybe we assume that both sentences are “similar” in theme. Whereas if the vectors are orthogonal, then we assume the sentences are independent or NOT “similar”. Depending on your usecase, maybe you want to find very similar documents or very different documents, so you compute the cosine similarity.

I want to motivate cosine similarity with a (not so rigorous) background discussion so we can understand where the measure comes from, especially given that the math only assumes basic linear algebra and high school geometry skills.

The geometric definition of the dot product:

But why do we care about cos of theta? Where does trig fit in with the dot product? Who thought of that? The answer comes from the law of cosines. A great walkthrough is available on the proof wiki.

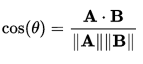

Intuitively, the cos(angle) will be 0 when the angle between vectors is such that the vectors are orthogonal. If the vectors are orthogonal, we think of them as linearly independent. If we’re looking for “similar” vectors, we probably don’t want them to be independent! Ideally, we want the cos(angle) to be as close as possible to 1. We think of the vectors as oriented in the same direction or if they’re sentences, perhaps they have the same “meaning”. Typically we compute the cosine similarity by just rearranging the geometric equation for the dot product:

A naive implementation of cosine similarity with some Python written for intuition:

Let’s say we have 3 sentences that we want to determine the similarity:

sentence_m = “Mason really loves food”

sentence_h = “Hannah loves food too”

sentence_w = “The whale is food”

For this example don’t care about the “meaning” of each word, we’re just going to compute counts:

sentence_m: Mason=1, really=1, loves=1, food=1, too=0, Hannah=0, The=0, whale=0, is=0

sentence_h: Mason=0, really=0, loves=1, food=1, too=1, Hannah=1, The=0, whale=0, is=0

sentence_w: Mason=0, really=0, loves=0, food=1, too=0, Hannah=0, The=1, whale=1, is=1

Looking at our cosine similarity equation above, we need to compute the dot product between two sentences and the magnitude of each sentence we’re comparing.

import numpy as np

def cos_sim(a, b):

"""Takes 2 vectors a, b and returns the cosine similarity according

to the definition of the dot product

"""

dot_product = np.dot(a, b)

norm_a = np.linalg.norm(a)

norm_b = np.linalg.norm(b)

return dot_product / (norm_a * norm_b)

# the counts we computed above

sentence_m = np.array([1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0])

sentence_h = np.array([0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0])

sentence_w = np.array([0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1])

# We should expect sentence_m and sentence_h to be more similar

print(cos_sim(sentence_m, sentence_h)) # 0.5

print(cos_sim(sentence_m, sentence_w)) # 0.25Final thought questions to ponder:

- How many ways can a given vector be parallel to another?

- How many ways can a given vector be orthogonal to another?